In two weeks, Dodger Stadium, after 42 years, will finally host the MLB All-Star Game again. Stars will descend. Celebrities will surface. Major League Baseball will cash checks.

Just a few months ago, reaching the glitzy checkpoint was a pipe dream. Remember that? When the owners and MLB Players Assn. nearly didn’t come to terms on a collective bargaining agreement to avoid shortening the season?

The two sides ended the drama when they reached a deal March 10. But one piece remained unsolved, kicked down the road for future headaches.

The union has until July 25 to decide whether to agree to allow MLB to implement an international draft in exchange for removing draft-pick compensation. The union wants neither. It resents having draft-pick compensation tied to free agents because it has proven to limit their earning power. And it has held steady for years on holding off the international draft for several reasons, including the fear of further restricting compensation and players losing the freedom to pick their team.

That could change this time around.

More than 15 executives, agents and players with experience in the Latin American amateur baseball scene were interviewed for this story. Some want the international draft. Others don’t. All agreed the current system is a mess needing significant changes.

MLB contends an international draft would mitigate the problems plaguing the market, particularly in the Dominican Republic, ranging from illicit early agreements between teams and 13-year-old boys to performance-enhancing drug use to unbridled corruption, while admitting it doesn’t effectively police the current system.

The San Diego Padres’ Fernando Tatis Jr. argues the international baseball draft would kill player development in his home country.

(Gregory Bull / Associated Press)

Prominent players — current and former — have expressed both caution and support. David Ortiz, a Hall of Famer from the Dominican Republic, said he’s open to the idea but worried about the implementation. San Diego Padres star Fernando Tatis Jr., a Dominican, said the draft would “kill” baseball in his country because he believes a draft would produce fewer opportunities for players. In March, New York Mets shortstop Francisco Lindor, a member of the union’s eight-player executive subcommittee during CBA negotiations, tweeted that the “international draft is about dividing players.”

On the other side, Venezuelans Bobby Abreu and Carlos Guillen, both of whom run academies in their home country, are among the notable advocates.

Those against the draft offer different reasons, but they center their rationale around one argument: The problems in Latin America exist because teams disregard rules knowing the league won’t enforce them.

“The reason that they want to implement a draft is because the teams themselves corrupted the system down there so poorly,” said one prominent agent who spoke on condition of anonymity. “The scouts are robbing from the teams themselves. Some of the scouts write a half-a-million-dollar check to the kid but they actually wrote a million-dollar offer to the organization and they pocket the difference. This has been going on forever. So, they created their own s—.”

Last month, Manfred acknowledged that form of corruption, specifically referencing Dominican Republic, in a news conference at the end of the league’s owners meetings.

“Our efforts to rein in corruption in the Dominican have been ongoing and legion,” Manfred said. “It’s easy to say that it’s the people that cut thechecks that are engaged in corruption. But you know somebody’s taking the check, right?”

The quote peeved the union, setting the stage for a final round of negotiations to discuss not just the mechanism to acquire players, but the infrastructure necessary to develop them in a vast, diverse region.

The league has proposed an annual 20-round international draft beginning in 2024. The 600 picks would be hard-slotted, meaning there would be no room for negotiations for signing bonuses, and tradeable. The top pick would receive about $5.25 million, and so on. The draft order would rotate by group every year, regardless of win-loss record. Undrafted players could sign for a maximum of $20,000. The age minimum of 16 would remain the same.

In the proposal, players eligible for the draft would be the same players eligible to sign as international free agents. That includes Japanese players before they sign with a team in Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB). Once a player joins the NPB, they would have to abide by the posting system agreed to among the leagues.

For example, Shohei Ohtani would have been subject to the draft out of high school and again when the Nippon-Ham Fighters posted him in 2017 because he was still classified as an international amateur, which would have left him without a chance to choose where he played in the majors. The league, however, is willing to negotiate the threshold for Japanese players with the union, according to a person with knowledge of the situation.

The Angels’ Shohei Ohtani would have been subject to the international draft if it had been in place when he was leaving Japan to join Major League Baseball.

(Jae C. Hong / Associated Press)

The league’s proposal would also include Cubans who establish residency outside of Cuba in the draft. It wouldn’t include Puerto Rico or Canada, which are part of the domestic draft with the United States.

MLB says the plan would guarantee that clubs would spend at least $20 million more than the last international signing cycle, maintain the yearly number of international amateur signings and provide more chances for older players in the market.

“We think this is the best way to fix a broken system and will abide by the MLBPA’s decision as part of the CBA agreement we made in March,” MLB said in a statement.

People against the proposal named a few issues. Prejudiced overreach in draft preparation. Smaller signing bonuses compared to the domestic draft. Fears that MLB wouldn’t provide sufficient resources for player development. A uniformity in player discovery that would hinder clubs that have successfully navigated the Latin American market while helping organizations that have made minimal investment in the region.

The problems are the worst in the Dominican Republic and Venezuela for one reason: The money is the biggest there.

In the Dominican Republic, people realized developing players was good business so trainers, known as buscones, surfaced to pull children from school to practice baseball full-time at 12 and 13 years old.

Former Boston Red Sox star David Ortiz, who is from the Dominican Republic, says he is open to MLB launching an international draft but he worries about the implementation.

(Adam Glanzman / Getty Images)

As more Dominicans became big league mainstays, teams gained confidence to increase spending and a multimillion-dollar industry was created with trainers usually taking a 50% cut. That money is often split among other “investors” who fund the player’s development in exchange for a portion of the signing bonus.

Problems always existed, but they escalated when MLB imposed spending caps on its clubs in the international amateur market in 2012 and stricter limits in the previous CBA, according to people with knowledge of the situation. The owners’ money-saving measures created an annual rush to grab a piece of a team’s pool money before it’s gone. A domino effect began. Early agreements, made two or three years before a player turns 16, became the norm.

“There’s so much going on down there that needs to be fixed,” said Hanser Alberto, a Dodgers infielder from the Dominican Republic.

A typical example: A trainer and an MLB team’s scout make a nonbinding handshake deal for a player two years before he’s eligible to sign. That player is then barred from being seen by other teams’ scouts to maintain the agreement.

That unofficial protocol has created problems. At the top of the list is PED use. Feeling the pressure to reach a verbal agreement, trainers have children as young as 12 years old take drugs to impress scouts. While most prevalent in the Dominican Republic, it also happens in Venezuela, according to people with knowledge of the situation.

MLB maintains a draft would motivate trainers to keep their prospects on the field for exposure ahead of the draft, allowing teams to make more informed talent evaluations while being drug tested randomly for the nine months leading up to the draft.

César Suárez, a former minor leaguer whose father has scouted for the New York Yankees for 30 years, now works as an agent in the United States and operates an academy in Venezuela, his home country. He explained it’s not uncommon for teams to reduce a player’s signing bonus after an early agreement because the player didn’t develop as expected or a red flag emerged during his physical.

“The draft doesn’t solve everything, but it solves some of these problems, including the early agreements,” said Suárez, who primarily represents Venezuelan major leaguers. “It’d mean less money for us, but it’d be a cleaner, more transparent business.”

David Ortiz, right, and Francisco Lindor, left, are among the current former players who have weighed in on the potential impact of the international baseball draft.

(Ron Schwane / Associated Press)

Money laundering is another issue in the Dominican Republic, according to people with knowledge of the situation, as the dollars and stakes have increased.

“When you allow for a system with this type of corruption, it draws people who can handle stuff like that, money laundering,” a team executive said. “Shady characters that are capable of pulling this stuff off.”

Rafa Nieves is another former minor leaguer from Venezuela who became an agent in the United States. Unlike Suárez, he sees the draft as a net negative.

“I’m not pro draft,” said Nieves, who represents several major leaguers from the Dominican Republic and Venezuela. “I think it would be a loss for the young kids in the international market. I’m in favor of a free market, of giving them a chance to pick where they work. The system is a disaster, no doubt about it, but a draft wouldn’t solve it.”

While antidrafters acknowledged early agreements would be all but eradicated, a few argued draft-pick manipulation would be simple to execute. Multiple people predicted kickbacks wouldn’t stop with hard slots because “it’s rolling the dice” with prospects beyond the top tier. As a result, they argued, scouts could reach kickback agreements with agents if they convince their team to select the player earlier than projected.

“Nobody is going to know the difference between the 55th and 88th prospects,” one agent said.

The union has also contended that MLB’s proposal is “discriminatory” compared to the domestic draft, citing that the slot money for the top pick is around $3 million less and PED testing would be more stringent for prospects. In the domestic draft, the top 300 players are subject to random PED testing upon registering for the draft. In MLB’s international draft proposal, every prospect would be subject to testing and trainers would face penalties.

People against the draft also wondered if fewer would be incentivized to invest in children, which would create a vacuum in development. MLB’s proposal calls for the creation of a free league across the Dominican Republic, supporting leagues in other countries, and investing in fields and equipment. MLB and the union declined to share the amount of money the league proposed to spend in infrastructure, but the union contends it isn’t enough.

“Our mindset on this kind of stuff is wait for things to play out,” said Andrew Friedman, Dodgers president of baseball operations. “And if things change, wrap our arms around it and figure out the best way to operate. I can make arguments for and against the international draft as it pertains to the Dodgers. But it doesn’t matter much.”

The road to this point began in the 1980s with the Dodgers leading the way in a very different world.

The Dodgers visualized an opportunity to tap into a deep talent pool and acted on it in 1987, opening the first MLB-affiliated academy in the Dominican Republic behind longtime scout Ralph Avila. It was a pioneering decision. Dominicans, and Latinos at large, had reached the major leagues for decades and with greater frequency in the 1980s. The Dodgers envisioned more.

The franchise, as a result, became the leaders in discovering and cultivating Dominican talent over the next decade, jump-starting a surge in Dominicans — and, indirectly, Latinos from other countries — across the majors. By 2003, all 30 MLB franchises owned an academy in the Dominican Republic.

Dodger Brusdar Graterol has not been able to visit family for years because of the threat of kidnapping in his native Venezuela. The unstable political climate has hindered baseball player development in the country.

(Dustin Bradford / MLB Photos via Getty Images)

Teams believed academies were worthy investments because, plainly, players were bargains. Hundreds of players signed never came close to playing for the Dodgers, but the few successes outweighed the failures.

This season, 99 Dominican-born players made opening day rosters — more than any country besides the U.S. Venezuela is next with 67. Dodgers reliever Brusdar Graterol was one of the 67 Venezuelans.

Graterol’s mother sends him videos from Venezuela of his youngest nephew, 11-year-old Ichiro, throwing a baseball against the wall at 5 a.m. and his older brother, 13-year-old Dominic, playing a slick shortstop. They’re the sons of Graterol’s brother, who died when the boys were young. They want to play in the major leagues.

They live in Calabozo, a tiny inland town in Venezuela. Graterol is from there, but he hasn’t returned to Venezuela in six years.

“I feel 90% safe going back,” he said, “but not 100%.”

While corruption in amateur baseball circles is notorious in the Dominican Republic, Venezuela has its own unique problems within the international baseball market. At one point, 23 MLB teams operated academies in the country. In 1997, a Venezuelan Summer League was created, 12 years after a Dominican league was established. Baseball was booming.

That summer league doesn’t exist anymore and those academies have been shut down because of the nation’s political conflict and economic turmoil over the last decade. For Venezuelan major leaguers, the instability has created security concerns. Many, like Graterol, don’t visit during the offseason.

For the youngsters hoping to emulate them, the situation has complicated the process. Travel restrictions — it’s illegal to fly directly from the U.S. to Venezuela — and safety fears have dwindled the amount of time MLB club executives spend in the country. Suarez gave an example of an official in an organization’s international scouting department who visits the Dominican Republic almost every month but hasn’t been to Venezuela in three years.

When important team decision-makers do visit, their visas are for a very limited time, according to people with knowledge of the situation. As a result, Venezuelan players have traveled to neighboring Colombia, the Dominican Republic and other countries for better exposure.

“Players in Venezuela are going to take their first deal, the first offer that they get because that’s life-changing money,” a team executive said. “Whereas in the Dominican, it’s a little bit more comfortable so a lot of these guys are willing to wait out to develop more and turn into a more valuable prospect.”

Substantial signing bonuses have still gone to Venezuelan prospects. In January, 14 Venezuelans signed for more than $1 million, according to the website Spotrac, compared to 18 Dominicans.

But some Venezuelans, including Abreu and Guillen, have maintained a draft would give prospects more time to develop — perhaps affording older players and late bloomers a chance to sign — and more money.

The list of top bonuses is dominated by the two countries every year while others — Mexico, Panama, Colombia, Aruba, Curacao, Nicaragua, the Bahamas and others — lag behind.

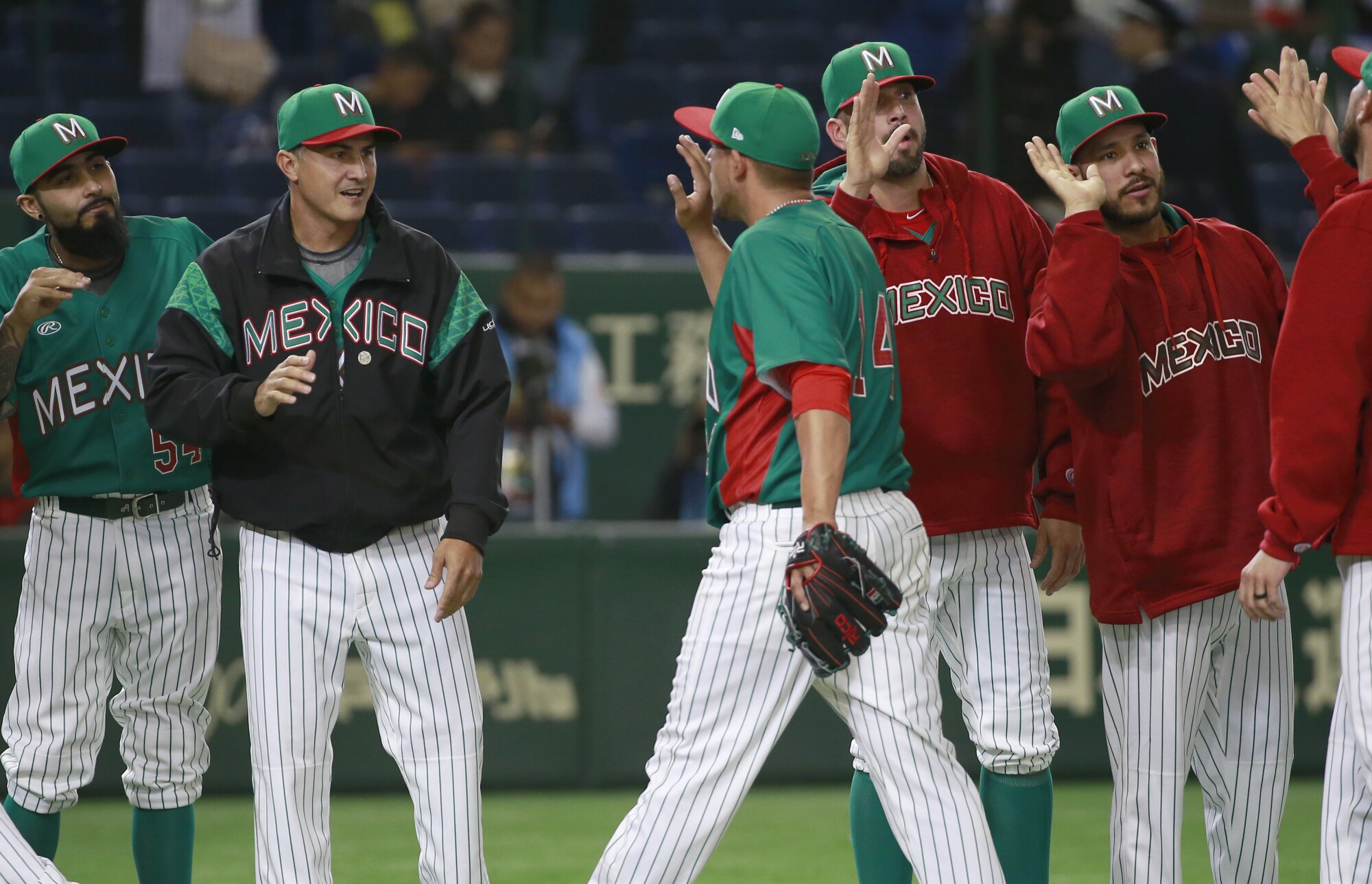

Mexico’s manager Edgar González, second from left, celebrates with his team after a win over Japan during the World Baseball Classic in 2016.

(Shizuo Kambayashi / Associated Press)

That isn’t a coincidence, according to Edgar González. The former major leaguer — and Adrian González’s older brother — operates a baseball academy in Tijuana. He said teams earmark little money for Mexicans after spending most of it in the Dominican Republic and Venezuela since the spending limits were imposed a decade ago.

“They come to Mexico with $100,000 for five players,” González said. “And they’ll say, ‘I know the kids worth a lot more, but this is what we have.’”

González said Mexican prospects also “get the short end of the stick” because they develop later than in other countries since they rarely stop attending school to train full time. Bonuses for most Mexican prospects, he said, haven’t topped $20,000 in recent years. He said 25 players from his academy have signed since opening “but all for very small bonuses.” Consequently, the academy has lost money every year and currently has fewer than 10 players after beginning with 40.

Another layer unique to Mexico is the presence of its professional league. González said teams run their own academies that compete with independent efforts. The clubs, according to González, regularly block players from independent academies, pushing them to sign with major league teams for little money.

“The draft would be such a good thing for Mexico,” González said.

It’s just one perspective to consider for a measure that would impact a complicated region with different baseball ecosystems, upending a system that has produced some of the sport’s brightest stars.

MLB believes it’s a necessary change. The union has disagreed. An answer could come by the end of the month.

[ad_2]

0 comments:

Post a Comment